Both flax and hemp plants have long been cultivated and used by humans for their extracts and fibers. Uses of these plants include rope, cord, sackcloth, and clothing. Flax plants have been more commonly associated with finer cloths, while hemp plants have been more often linked to thicker yarns, hence the preference for the latter in the industrial realm.

While flax cultivation has been uninterrupted over the centuries, hemp cultivation experienced legal restrictions in the early part of the 20th century due to the mistaken assumption that it produces significant amounts of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main intoxicating compound found in the cannabis plant. But the alleviation of these regulations in the US and the eventual emergence of the 2018 Farm Bill led to the resurgence of hemp cultivation and extraction.

Now, there is more focus being placed on both hemp and flax plant cultivation and the extraction of cellulose fibers. [1] The extraction of fibers is being done for a variety of purposes. Bast fibers are collected from the phloem surrounding the core of dicotyledonous plants and give strength and support.

Industrial advancements have decreased the use of bast fibers. That said, a heightened focus on sustainability and the environment has revitalized interest in bast fiber utility.

The fiber cells of the plants develop into layered structures as they mature into young fibers. As they elongate, the cell walls are made up mainly of cellulose, pectins, and hemicelluloses. To extract fibers from the stems of flax and hemp plants, the process of retting must first occur, which essentially weakens the connection between the fibers and their surrounding material.

Retting can be done in several ways. Traditionally, hemp is cut and exposed to weather in the field. Fungi and bacteria naturally break down the stalks. Water retting places the hemp in water, where it is more quickly broken down by aerobic bacteria, although the costs of drying the fibers and treating wastewater often prove prohibitive. Emerging industrial options include enzymatic applications, particularly pectinases, as well as chemical treatments and physical separations (e.g., relying on microwaves).

Following this, a mechanical process separates the bundles of fiber. The woody core is first broken up by pulverizing the stems, followed by the removal of the broken pieces (scutching) and short fibers (hackling).

The final product results in individual fiber bundles that can be further split into finer strands, or elementary fibers. It’s this material that can be used for industrial purposes, such as the manufacturing of textiles. For applications that require finer fibers, such as in the use of creating fine clothing, the fibers need to undergo additional chemical processing to further separate the bundles into finer strands.

This cottonization requires delignification (removing the lignin). Potential industrial treatments include enzymatic, microbial, and chemical treatments, the latter of which includes common pulping processes like kraft, soda, and sulfite.

The increased use of flax and hemp fibers may replace other components used to create textiles, wood fiber, glass fiber, and clothing, among others. Right now, flax and hemp fiber production volumes are heavily overshadowed by the outputs of other materials, though there are efforts in place to boost flax and hemp fiber output.

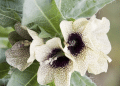

Photo by Harrison Haines from Pexels

References:

- Manian AP, et al. Extraction of cellulose fibers from flax and hemp: a review. Cellulose. 2021;28:8275–8294. [Impact Factor: n/a; Times Cited: 5.044]