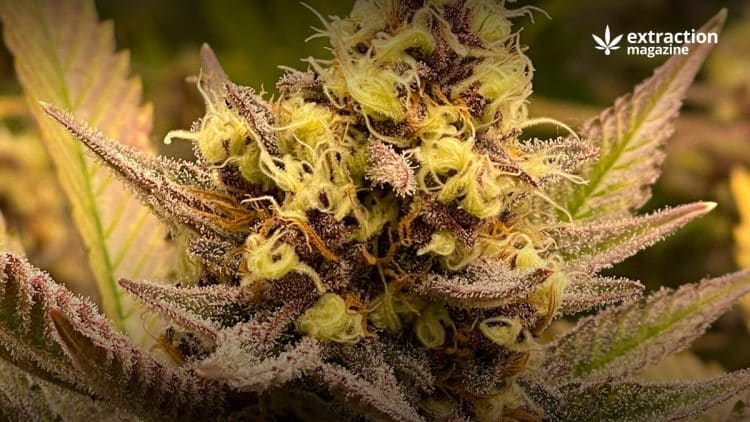

Cannabis is one of the most controversial plants in our society today. For some, it is effective as a medicine or a profitable agricultural commodity. For others, it is a dangerous drug that leads to addiction and the potential downfall of society. Cannabis has played a vital role in human history for a variety of reasons. Setting aside the fact that it is one of the oldest cultivated plants, some scientists even believe that it helped to play a role in human evolution.

The Early Days of Cannabis

While fossil records indicate that cannabis cultivation stems all the way back human occupation in Africa, the first records of cannabis growth came from Ancient China. Farmers along the Yellow River first started to grow cannabis alongside their rice, beans, millet, and wheat crops approximately 4000-6000 years ago. The first known usage of cannabis came with the publication of the Xia Xiao Zheng by Emperor Shen Nung around 2800 BCE. Shen Nung is seen as the father of Chinese medicine, and he promoted cannabis in several traditional Chinese treatments.

From China, cannabis spread to other ancient civilizations. Ancient texts show that cannabis was used by the Hindus, Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans, often citing similar medical uses to today. The maladies varied by populations, but cannabis was often used to treat things like pain, inflammation, arthritis, depression, and a loss of appetite. With the Roman Empire, cannabis then spread to the rest of Europe, and eventually the Americas as well.

The Split Between Indica and Sativa

Before continuing with the human history with cannabis, it is worth noting a significant moment in the natural history of the plant. The story here is mostly a theory, but it attempts to explain the main differences between indica and sativa. Sativa is tall, slender, and tends to have an energizing effect on its users. Indica, on the other hand, is shorter, bushier, and produces drowsiness and lethargy.

Evidence suggests that there is no genetic difference between these versions of the plant, so what accounts for these variations? The prevailing theory is that when cannabis moved from China to India, the two plants experienced centuries of isolation from one another. The Himalayas created a geographic barrier between the two areas. This isolation lead to gradual changes due to natural selection that benefited each version of cannabis to thrive in their respective reasons. Western China tends to be cold and dry, whereas the Indian subcontinent is hot and humid. These dramatically different environments allowed cannabis to grow differently, hence the two versions we know of today.

Cannabis Through The Middle Ages

Thanks to the Roman Empire, cannabis spread across Europe, where it became more valued as an agricultural commodity than as a medicine.

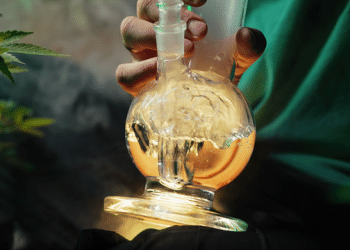

While the medical potential was still utilized, hemp, a cannabis with low content of the psychotropic tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), became more common in Europe. This is because hemp was one of the most useful plants for the Europeans at the time. They used it as a food source, but mainly for textile production, and for making household items like baskets or furniture.

While the applications varied by culture and by region, it proved especially useful during the European colonial expansion. Hemp fibers were woven into ropes and sails that helped Europeans to extend their empires across the world. Hemp was seen as such a vital plant, that when the American colonies were formed, mandatory growth laws were implemented in Jamestown, Virginia, Massachusetts, and Connecticut.

The industrialized use of hemp still continues in Europe, where it is classified as a novel food product. Across the Atlantic, though, attitudes began to change during the 20th century.

The Prohibition Era

Starting in the early 1900s, the American attitude toward cannabis began to shift due to various political and business interests. It all started with the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. Prior to this act being passed, there was no regulation about what was safe for Americans to consume. Heroin was being used as a cough suppressant and arsenic was used to treat syphilis prior to the passage of this law.

Cannabis was not necessarily a major concern. It was included in some medicinal tonics, but most regulators didn’t know or care about its usage when more harmful substances were going unregulated. That all changed several decades later when cannabis became the primary target for two powerful men.

The first was the Head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics Henry Anslinger. His true motivations have been debated by historians, but ultimately cannabis was his lever towards political power.

Anslinger made it his personal mission to see cannabis outlawed in the United States, and he was aided by William Randolph Hearst, the newspaper magnate.

For Hearst, the motivation was largely economically based. He saw hemp as a cheaper alternative that could replace the paper he printed with. Not wanting his massive lumber holdings to suffer a loss, Hearst began a public campaign to spread misinformation about cannabis.

This led to a period colloquially known as “Reefer Madness” which culminated in the passage of the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937. This law established a taxation system for cannabis, thereby determining who was eligible to sell it. If no tax stamp was issued to the vendor, it was considered illegal to buy, sell, or possess.

In the 1960s, the next generation began to adopt a pro-cannabis stance with their counter-cultural revolution. The hippies had a relaxed attitude towards cannabis and other psychedelics, leading to a revival in the drug’s popularity.

This was the case until the 1970s, when Richard Nixon chose to make a stand. Nixon felt that drug use was getting out of control, due to rising reports of heroin addiction from returning Vietnam War veterans. As a response, he declared a War on Drugs, ramping up the Federal government’s stance against cannabis to the highest point it had been in years. The War on Drugs actually was intended to serve a more insidious purpose.

The 1970s were a time of political chaos, and Ehrlichman testified that in 1968, Nixon had two political oppositions: the anti-war left and the Civil Rights movement. Though Nixon knew that he couldn’t outlaw these political opinions, or the freedom to express them, so Ehrlichman claims that Nixon chose to tie these two political movements to drug use. This gave the president an effective tool to crack down on political dissent, with a palatable justification for the American public.

At the time, the hippies and the anti-war left were tied to cannabis, while black people were tied to heroin. As the War on Drugs has progressed over the last several decades, other groups have been effectively targeted through the use of drug possession, including immigrants and minorities.

The Cannabis Renaissance

Coming into the 21st century, cannabis is starting to see a resurgence in relevance. It is too early to say that full, global acceptance is coming, but cannabis legalization is reaching a transitional point. Several countries around the world have opted for full legalization, including Uruguay, Canada, Israel, and Malta. Others, like Germany and Thailand, have announced plans to relax their laws regarding cannabis, but neither have implemented these changes yet.

Though Cannabis remains illegal on a Federal level in the United States, a grassroots movement is seeking to change that from the ground up. Currently, 37 states and US territories allow medical cannabis consumption, meaning it is available in some form in more than half the states. [20] With this increased regulation comes additional data as well. This applies to medical applications, personal consumption, and macroeconomic effects like crime stats and damages to communities. It is difficult to say with certainty, but general trends are pointing towards more acceptance of the plant, especially as more and more communities chose to embrace legalization without seeing major negative consequences.

References:

- Duvall, C. S. (2019). A brief agricultural history of cannabis in Africa, from prehistory to canna-colony. DOAJ (DOAJ: Directory of Open Access Journals). https://doi.org/10.4000/echogeo.17599

- Kumar, T. H. (2017). Human Evolution and Cannabis: The Ultimate Gift. Lulu Press, Inc.

- Lu, Xiaozhai, and Robert C. Clarke. “The cultivation and use of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) in ancient China.” Journal of the International Hemp Association 2.1 (1995): 26-30.

- Pisanti, S., & Bifulco, M. (2019). Medical Cannabis : A plurimillennial history of an evergreen. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 234(6), 8342–8351. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.27725

- Kuddus, M., Ginawi, I. A., & Al-Hazimi, A. M. (2013). Cannabis sativa: An ancient wild edible plant of India. Emirates Journal of Food and Agriculture, 25(10), 736. https://doi.org/10.9755/ejfa.v25i10.16400

- Russo, E. B. (2007). History of Cannabis and Its Preparations in Saga, Science, and Sobriquet. Chemistry & Biodiversity, 4(8), 1614–1648. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbdv.200790144

- Brunner, T. F. (1977). Marijuana in Ancient Greece and Rome? The Literary Evidence. Journal of Psychedelic Drugs, 9(3), 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.1977.10472052

- Sumler, Alan. Cannabis in the Ancient Greek and Roman World. Lexington Books, 2018.

- Hillig, K. W. (2005). Genetic evidence for speciation in Cannabis (Cannabaceae). Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution, 52(2), 161–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-003-4452-y

- Skoglund, Git, Margareta Nockert, and Bodil Holst. “Viking and early Middle Ages northern Scandinavian textiles proven to be made with hemp.” Scientific reports 3.1 (2013): 1-6.

- Deitch, R. (2003). Hemp: American History Revisited: The Plant with a Divided History. Algora Publishing.

- Office of the Commissioner & Office of the Commissioner. (2019, April 24). Part I: The 1906 Food and Drugs Act and Its Enforcement. U.S. Food And Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/changes-science-law-and-regulatory-authorities/part-i-1906-food-and-drugs-act-and-its-enforcement

- Heroin Bottle | DEA Museum. (n.d.). https://museum.dea.gov/museum-collection/collection-spotlight/artifact/heroin-bottle#:~:text=In%201898%2C%20Bayer%20%26%20Co.,as%20an%20effective%2C%20safe%20treatment.

- Frith, John. “Arsenic-the” poison of kings” and the” saviour of syphilis”.” Journal of Military and Veterans Health 21.4 (2013): 11-17.

- Solomon, R. C. (2020). Racism and Its Effect on Cannabis Research. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research, 5(1), 2–5. https://doi.org/10.1089/can.2019.0063

- Gieringer, D. H. (1999). The Forgotten Origins of Cannabis Prohibition in California. Contemporary Drug Problems, 26(2), 237–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/009145099902600204

- The Marihuana Tax Act of 1937 – Full Text of the Act. (n.d.). https://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/hemp/taxact/mjtaxact.htm

- Wood, E., Werb, D., Marshall, B. D., Montaner, J. S. G., & Kerr, T. (2009). The war on drugs: a devastating public-policy disaster. The Lancet, 373(9668), 989–990. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60455-4

- Nunn, K. (2002). Race, Crime and the Pool of Surplus Criminality: Or Why the “War on Drugs” Was a “War on Blacks.” UF Law Faculty Publications. https://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1178&context=facultypub

- State Medical Cannabis Laws. (2023, March 13). https://www.ncsl.org/health/state-medical-cannabis-laws#:~:text=A%20total%20of%2037%20states,medical%20use%20by%20qualified%20individuals.