Dipping deeper into the annals of scientific literature, we found a neat article from 1960 that divulged the antibiotic activity of a peyote extract (thank you Lance Griffin!). [1] The Arizona State Department of Liquor Control had confiscated “several sacks of peyote” and subsequently gifted the cacti to the authors of the study for scientific investigation. It was already known in 1960 that peyote had medicinal purposes such as providing therapeutic benefits for treating “toothaches, pain in childbirth, fever, breast pain, skin diseases, rheumatism, diabetes, colds, and blindness.” [2] The Mexican Pharmacopoeia even provides the term empeyotizarse, which means to treat oneself to alleviate hangovers. [3]

The peyote extract was liberated from the host cacti using various solvents. Ethanol (95%) produced an extract that was resistant to bacterial growth, so the researchers mixed peyote with ethanol using a 25:1 ratio (w/v). They blended this mixture for 15 minutes and filtered out the pulp raffinate with filter paper.

The ethanol was removed from the extract under vacuum such that the ingredients that were not soluble in water (which provided the other 5% in the ethanol) dropped out as a precipitate. Additional water was added to the aqueous phase at a similar volume (1:1) and the solids were filtered out. The remaining liquor was tested against 20 bacterial fiends including Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, Sarcina lutea, Bacillus subtilis, Neisseria catarrhalis, and Escherichia coli.

Having demonstrated positive results, the liquor was further processed by first acidifying with hydrochloric acid to pH 2 and holding that solution at 5°C for 24 hours. A precipitate formed over this duration and was subsequently filtered. The precipitates (the one from the ethanol evaporation and this new one) were redissolved and tested for antibiosis. The liquor here was maize hued and the researchers wanted to further refine to strip out the color, so they turned to activated charcoal and diatomaceous earth. Rendered colorless, this new liquor was evaporated to dryness, leaving another precipitate.

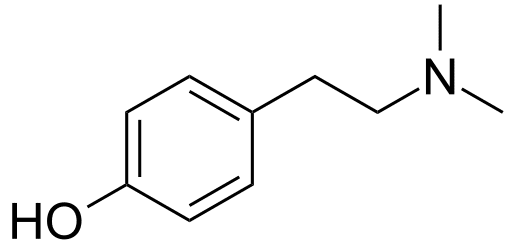

This precipitate was dissolved in methanol which enabled insoluble contaminants to be removed, further purifying the solution. The liquid was again evaporated and the final crystalline substance, termed peyocactin (aka hordenine, aka N,N-dimethyltyramine) was hypothesized as containing the key antibiotic constituents. The final solution contained the isolated peyocactin in distilled water, pH 7.

The peyote extract was so good at inhibiting the growth of S. aureus colonies that the researchers evaluated 18 more penicillin-resistant strains of this bacteria. All were inhibited by the peyocactin. The researchers moved to a murine study and found that the peyote extract protected the mice from fatal S. aureus.

The rise of natural psychedelics like peyote and the molecules therein returns us to plants that have been in terra for millennia, ripe for the plucking, used whole or as extracts. Perhaps the next few years will see humankind evolve out of silly stigmas and tragic taboos to grasp hold of plants that can help us in life-enhancing and empowering ways.

References

- McCleary J, Sypherd P, Walkington D. Antibiotic activity of an extract of peyote (Lophophora williamii (Lemaire) Coulter). Economic Botany. 1960;14(3):247-249. [journal impact factor = 1.775; times cited = 7 (Semantic Scholar)]

- La Barre, Weston. The peyote cult. Yale Univ. Publ. in Anthropology #19, 1938.

- Schultes RE. The appeal of peyote (Lophophora williamsii) as a medicine. Am Anthro. 1938;40:698-715. [journal impact factor = 1.788; times cited = 40 (Semantic Scholar)]

Image Credit: Frank Vincentz, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons