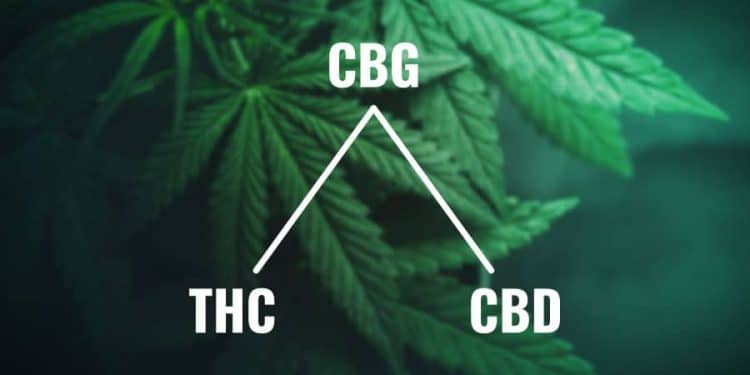

Despite being discovered in 1964 and called the “mother” of all cannabinoids, the “stem cell,” cannabigerol (CBG), has mostly flown under the radar that is generally occupied with tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). However, as our curiosity extends beyond the star cannabinoids, CBG might finally get the respect it deserves.

Why the “Mother” Cannabinoid?

The cannabinoid acids tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA), cannabidiolic acid (CBDA), and cannabichromenic acid (CBCA) are all synthesized from cannabigerolic acid (CBGA) within the plant as it develops. Enzymes like THCA synthase catalyze the reactions forming the other acidic species.

CBGA is usually found in small quantities in most cultivars. CBGA’s limited, natural concentration also means that much more biomass is needed to extract meaningful stockpiles of the molecule for scientific study. Crossbreeding, genetic editing, and synthesizing the molecule in a lab present some alternatives for maximizing access to CBGA, but the latter two, of course, aren’t without their concomitant controversies.

Like the other acidic cannabinoids, CBGA must be decarboxylated to produce CBG. Although CBG isn’t intoxicating like THC, it may have a lot to offer to medicinal cannabis users.

Medicinal Properties

Anti-Inflammatory

One study found that CBG reduced inflammation indicators in mice with inflammatory bowel disease and alleviated colitis, giving the researchers a reason to believe these properties are worth exploring in humans with the same disease. [1]

Neuroprotective

When tested on mice with Huntington’s disease, which is caused by brain nerve cell degeneration, CBG protected neurons and thus lessened motor deficits. [2]

Anti-Cancer

To begin with the prevalent important disclaimer, a study on mice with colon cancer found CBG to impede the colorectal cancer cells’ growth by blocking the receptors that stimulate this growth. This clearly is exciting news that will hopefully be followed up by more clinical research. [3]

Anti-Bacterial

The methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) microbial strains, as their name suggests, are notoriously resistant to traditional treatments, but not to CBG, along with four other cannabinoids that turn out to be the source of cannabis formulations’ mysterious powers against these sturdy bacteria. [4] While CBD and cannabinol (CBN) required lower concentrations to inhibit 50% of the bacterial growth, CBG was still more effective against some strains compared to some of the traditional drugs tested.

Appetite Stimulant

While CBD has clearly taken after its “mother” in the aforementioned regards, THC seems to have taken something from her as well — appetite stimulation. In a recent study, CBG caused rats to eat double the amount of food they normally do. Interestingly, CBG only increased the number of meals rather than the quantity eaten at each meal, which is probably some food for thought. [5]

Bladder Issues

CBG helped the lives of mice yet again, this time by easing bladder contractions. The study explored five cannabinoids, among which CBG and tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV) displayed the best results. [6]

Being the “stem cell” from which the other major cannabinoids originate is certainly a serious statement, and CBG backs it up in multiple studies that demonstrate versatile properties, albeit most often on mice. Advanced research and access to larger quantities of CBG will likely continue to spark further interest in the scientific community for unlocking what this molecule can offer us.

References:

- Borrelli, F. et al, “Beneficial Effect of the Non-Psychotropic Plant Cannabinoid Cannabigerol on Experimental Inflammatory Bowel Disease,” Biochem Pharmacol., vol. 85, no. 9, 2013, pp. 1306-16. [Journal Impact Factor = 5.009; Times Cited = 166]

- Valdeolivas, S. et al, “Neuroprotective Properties of Cannabigerol in Huntington’s Disease: Studies in R6/2 mice and 3-Nitropropionate-Lesioned Mice,” Neurotherapeutics, vol. 12, no. 1., 2015, pp. 185-199. [Journal Impact Factor = 5.719; Times Cited = 54]

- Borrelli, F. et al, “Colon Carcinogenesis is Inhibited by the TRPM8 Antagonist Cannabigerol, a Cannabis-Derived Non-Psychotropic Cannabinoid,” Carcinogenesis, vol. 35, no. 12, 2014, pp. 2787-2797. [Journal Impact Factor = 5.334; Times Cited = 92]

- Appendino, G. et al, “Antibacterial Cannabinoids from Cannabis sativa: a Structure-Activity Study,” J Nat Prod., vol. 71, 2008, pp. 1427-1430. [Journal Impact Factor = 4.257; Times Cited = 366]

- Brierley, D. et al, “Cannabigerol is a Novel, Well-Tolerated Appetite Stimulant in Pre-Satiated Rats,” Psychopharmacology (Berl), vol. 233, no. 19-20, 2016, pp. 3603-3613. [Journal Impact Factor = 3.875; Times Cited = 11]

- Pagano, E. et al, “Effect of Non-Psychotropic Plant-Derived Cannabinoids on Bladder Contractility: Focus on Cannabigerol,” Nat Prod Commun, vol. 10, no. 6, 2015, pp. 1009-1012. [Journal Impact Factor = 0.554; Times Cited = 16]

Image Credits: Zamnesia