Aristotle believed that matter was composed of four basic elements: earth, water, air, and fire. A fifth element was postulated, called the aether, or quintessence, or life force. When considering plants, this quintessence was thought to be their spirit – and this spirit could be extracted! [1] No doubt, you already knew this from experience with distilled spirits. And while we might revel in the bacchanalian concept of distilling alcohol, ancient cultures distilled grains like barely, wheat, and rice to produce their own fermented beverages. Thus, the story of distillation goes far back into human history.

Our ancestors thought that rainfall was caused by “vapour rising from the sea.” [2] As heat sources became commonplace, they likely witnessed condensation forming when vapor cools. Aristotle knew about this. You’ve also witnessed this at home when boiling a liquid on the stove. Droplets form as vapor collects on the lid and acquiesces to the lid’s cooler temperature.

A wonderful synopsis of early distillation practices reports that “ancient sailors in eastern seas thus obtained fresh water, for drinking, from sea water.” [2] Heating the seawater, and the subsequent cooling and collecting of the vapor, purified the water, leaving undesirable molecules like salt behind. The rudimentary distillation setup apparently consisted of the boiling seawater and a wet sponge/rag that served as the collection “vessel.” Periodically, the sailors would wring out the cloth, obtaining the purified water.

Some historians believe that the Christian Bible refers to distillation practices in the Gospel of Matthew in a line reading the “grass of the field which to-day is and to-morrow is cast into the oven.” The hypothesis is that plant matter was heated to remove fragrant molecules (terpenes) for downstream perfumes and medicines. And I know you want that grass to reference Cannabis sativa.

Pliny also reported the transformation of water into wine, or at least some other alcoholic beverage, saying “Oh! wondrous craft of the vices! by some mode or other it was discovered that water itself might be made to inebriate.” [2]

Ancient Egyptians also were instrumental in early distillation advances. Some of the writers of these accounts were executed for their refusal to adopt Christianity, and unfortunately, many written documents were destroyed. A schematic that survived can be seen in Figure 2 in reference 2 below.

Ancient Indians designed the Mysore still which was placed over a fire ignited in a hole in the ground. [2] A liquid made from rice, molasses, and cocoa-nut tree juice was added to the still, and the whole setup was covered with earth so that heat was retained. Once the liquid boiled, steam was condensed using a stream of cool water.

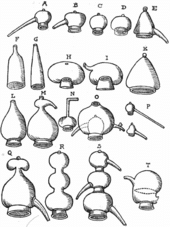

Not all early distillation designs lacked artistic creativity. Some 13th and 14th century French systems employed longer columns enabling a more concentrated brandy in one pass. These designs included a staggered, zig-zag pathway for the vapors to navigate (see Figure 14 in reference 2).

Some 16th century alembic manufacturers (alembic: distillation design using a rounded, necked flask and a long-necked cap for condensing vapors and transferring condensate to a receiver) got more creative, making their systems resemble an ostrich, or turtle, or hydra, which is my favorite, since it was designed to capture different chemical fractions in the hydra heads based on their condensability.

Our ancestors provided a rich foundation for modern distillation technology, whether your cup of tea is cannabis or corn. Stay tuned for the next fraction on the history of distillation where we’ll journey to Ireland and Kentucky at a minimum.

References

- [1] Sell, C. “Chemistry of Essential Oils.” Handbook of Essential Oils: Science, Technology, and Applications, edited by Hüsnü Can Başer, K., and Buchbauer, G., CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, 2016. [cited by 19 (ResearchGate)]

- [2] Fairley, T. “The Early History of Distillation.” Journal of the Institute of Brewing, vol. 13, no.6, 1907, pp. 559-582. [journal impact factor = 0.994; cited by 1 (Wiley)]

Image Credits: DrinkingCup.net, Wikimedia Commons (Swetapadma07: CC BY-SA 3.0), Wikipedia (public domain)